Tensor to Scalar Ratio

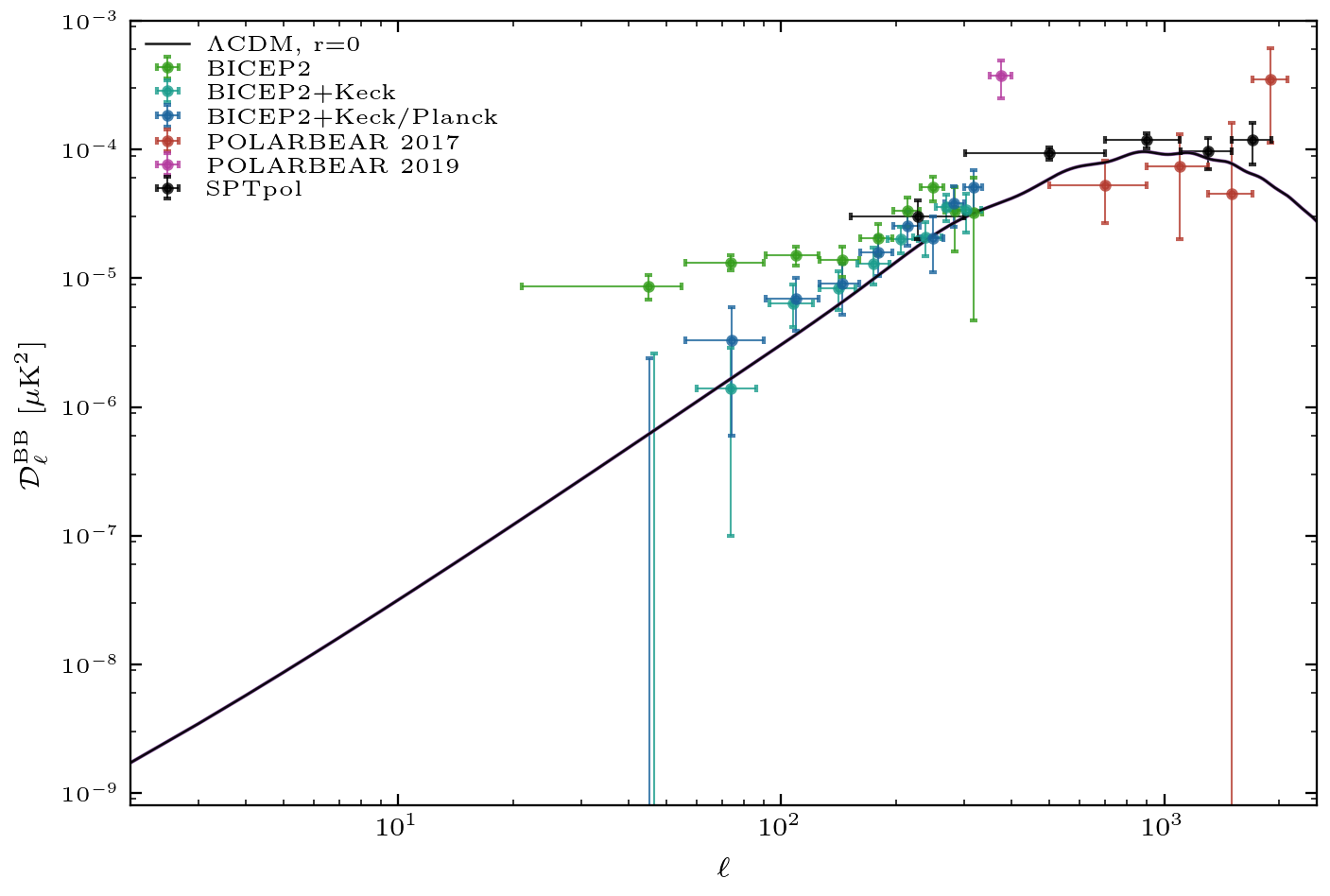

The tensor-to-scalar ratio \(r\) quantifies the relative strength of primordial gravitational waves compared to density fluctuations, and is defined as \( r \equiv A_t/A_s \), the ratio of the amplitudes of the primordial tensor and scalar power spectra. A nonzero value of \(r\) would leave an imprint in the CMB, most clearly in its polarization patterns. CMB polarization can be decomposed into two distinct geometries: E-modes and B-modes, which are named as such based on their respective curl and curl-free nature. These are sourced via different mechanisms. For example, when photons scatter off electrons at the surface of last scattering, they become effectively polarized. However, the resulting polarization directions must be either perpendicular or aligned with the photon wavevector. Thus, the scalar temperature fluctuations on the last-scattering surface can only impart a curl-free polarization pattern called E-modes. We are mainly focused on these modes since most of the perturbations we are interested in studying are scalar (e.g. temperature perturbations). Tensor perturbations, on the other hand, are not limited to sourcing only E-mode polarization patterns. These "swirling'' perturbations create both a curl-free E-mode and a curled B-mode patterns. As the tensor-to-scalar ratio increases, the contribution of these B-modes becomes larger, appearing as an excess of power in the BB polarization spectrum above the lensing-induced signal.

Since these primordial gravitational waves have wavelengths on the order of the size of the observable universe at that time (large angular scales, low multipoles), we expect the amplitude increase to manifest at these scales as well, trailing off at higher multipoles (smaller angular scales) due to Silk damping.

Accurate measurement of the tensor-to-scalar ratio will provide enormous insight into the mechanisms present in the early universe. Since B-mode polarization signatures are unique to tensorial sources like gravitational effects, their search directly targets these perturbations while avoiding the larger E-modes altogether. Among early-universe scenarios, inflation hypothesizes that the very early universe went through a period of accellerated expansion leaving behind a stochastic background of gravitational waves that produces a characteristic B-mode signal. In contrast, alternatives such as bouncing cosmologies, where the universe underwent a period of slow-contraction prior to the onset of the expansion, generally do not produce gravitational waves at an observable level. A confirmed detection (or absence thereof) of primordial B-modes will therefore play a decisive role in discriminating between competing models of the early universe.

Detecting such a signal, however, is extremely challenging. Experiments such as BICEP and POLARBEAR have already pushed the boundaries of B-mode observations, but several obstacles remain. Gravitational lensing by large-scale structure distorts E-modes into lensing B-modes, masking the primordial contribution, while astrophysical foregrounds — particularly thermal dust emission — can mimic the same pattern on the sky. The 2014 BICEP2 claim of a primordial detection, later attributed to dust, underscored the importance of careful foreground modeling. Current and upcoming projects such as the Simons Observatory and CMB-S4 are designed to meet these challenges, aiming to separate lensing and foreground contributions with sufficient sensitivity to isolate a primordial signal. Despite the obstacles, the promise of uncovering new physics from the earliest moments of cosmic history keeps the search for B-modes at the forefront of modern cosmology.